The Aba Women’s Riot of 1929 was a two-month rebellion waged by local market women from the Igbo tribe of southeastern Nigeria against the excessive powers of the British government and its warrant chiefs at the height of colonialism.

The rebellion was triggered by the imposition of exploitative tax policy on women, who were tax-exempt in the Igbo tradition. The plot and outcomes of this event provide just one example of Africa’s long history of embracing classical liberal values and provide a stark contrast to the deplorable state of human freedom across the continent today.

The British Structure of Failure

Learning from the shortcomings of France’s Assimilation approach in its African colonies and taking into account the unwillingness of the British government to financially commit to its protectorates, the governor-general in charge of Nigeria, Frederick Lugard, adopted a system of indirect rule. This system allowed traditional leaders and British-appointed warrant chiefs to serve as representatives of the Queen of England rather than having British personnel all over. It saved the colonialists a great deal of manpower, which it aggressively channeled into plundering mineral resources across Igboland.

But while the masters were busy using the colony’s resources to industrialize Britain, the warrant chiefs grew powerful and despotic. They extorted their subjects by imposing unreasonable fines and charges. They seized private properties at will and brutalized anyone who opposed their authority.

In contrast, in pre-colonial Igboland, leaders were always elected—not imposed. Their administrative systems were highly decentralized and egalitarian. They rejected any form of power concentration, instead decentralizing authority across age groups and clans that made up the community.

Enumerating Goats and Children in Taxes

In the 1920s, the British government was criticized for not developing the colonies despite having gained a great deal from them. This was the same time Britain was recuperating from the financial loss of World War I. To raise funds, the colonialists had to resort to internal means of revenue generation, which included a proposal to impose direct taxation on women and enumerating children, livestock, and other personal properties as taxable possessions.

To get their numbers right, the British organized a census, which the public quickly figured out was related to the new tax policy. Market women became worried about the possible effects of the new tax rule on their businesses and how they would keep up with the numerous financial burdens imposed by the warrant chiefs. They consulted the colonial government to preserve their tax-exempt status, but their plea was rejected. Resolving to preserve their liberty, they engaged in defiance, neither paying taxes nor welcoming any stranger to count their properties.

However, during one of the countings, an argument between a census officer and a widow in one of the villages resulted in an assault on the widow. The news reached a gathering of market women in the town square as they discussed the crazy tax policy. Furious about this, they mobilized their colleagues from neighboring villages and went to the local warrant chief’s office to demand his resignation.

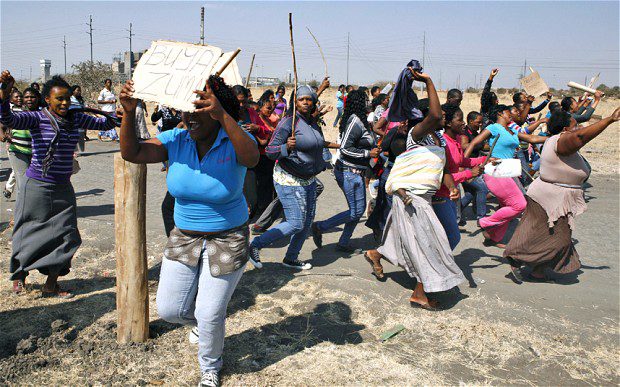

The protest would grow from a peaceful sit-in to the fiercest resistance the British ever faced across of their African colonies. It led to the severe destruction of government infrastructure and factories across Igboland, which colonial troops and police met with brutal force. Over 25,000 women were involved, dozens of whom were killed and severely beaten.

Within a short time, news of the resistance spread across the world, inspiring other minority groups in Africa. The rebellion did not, of course, end colonialism, but it reinforced the foundations of inclusive indigenous administration, and to some extent, the struggle for independence.

The State of a Dying African Tradition

The bravery of these women in preserving their properties and traditional rights by fighting a powerful system underscores Africa’s lost spirit of intolerance against tyranny.

Long before John Locke wrote The Two Treatises of Civil Government in 1689, which helped lay the intellectual foundation for the limitations of government, many African tribes lived in alignment with his propositions. They were anarchic and highly democratic communities thriving without central planning. Some of these included the Igbo, the Ijaw (Nigeria), the Tallensi (Ghana), the Logoli (Kenya), the Tonga (Zambia), and the Nuer (South Sudan), among many others.

Their great shortcoming was the failure to document their values and history. These values were put to the test during colonialism, and unfortunately, Africa lost its way of life amid the forceful amalgamation of different ethnic groups into colonial states. The Aba Women’s Rebellion is sadly one of the last accounts of the true African values. Writer Sam Mbah put it well in African Anarchism, where he noted:

To a greater or lesser extent, all of traditional African societies manifested “anarchic elements” which, upon close examination, lend credence to the historical truism that governments have not always existed. They are but a recent phenomenon and …while some “anarchic” features of traditional African societies existed largely in past stages of development, some of them persist and remain pronounced to this day.

Unfortunately, contemporary Africa is the opposite of what the region’s ancestors resolutely struggled to realize. The continent is lost in poverty while tyrants and their cronies loot its resources without being held accountable. The old are too afraid to sacrifice in resistance against their oppressors, while the young are stuck in a deep romance with the very philosophy that has made them poor. But for the few African libertarians today, the courage of the women of Aba should inspire more efforts to fight against that power.

Ibrahim B. Anoba is an African political economy analyst and a Senior Fellow at African Liberty. Tweet at him: @Ibrahim_Anoba